Austin Irwin

What is sportswashing?

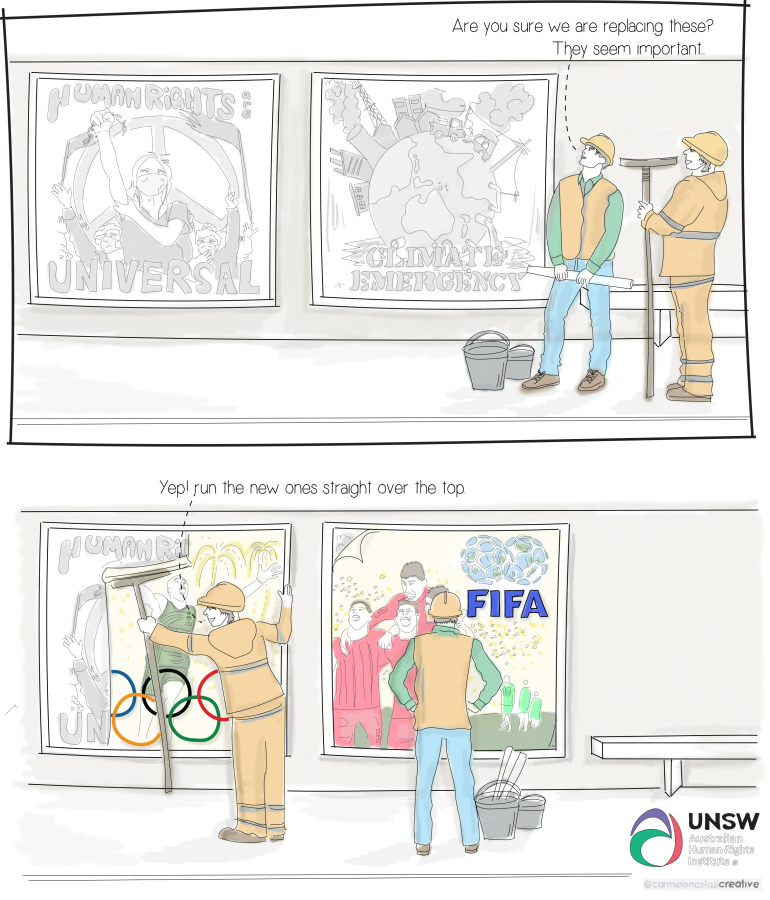

Sportswashing is the use of sport to redirect public attention away from unethical conduct. The intended effect is to improve the reputation of the offending entity, by using the immense popularity of sport to ‘wash’ away poor publicity. The most high-profile instances of sportswashing are carried out by authoritarian states that have committed human rights abuses, but commercial businesses also engage in the practice (e.g. to distract from climate-unfriendly activity).

What are some recent examples of sportswashing?

State-funded sportswashing will often use the hosting of global sporting events as a mechanism. Recent examples that have drawn criticism as incidents of sportswashing are the 2022 Winter Olympics held in China and the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar. There are also many recurring events hosted in authoritarian countries. These include cycling’s UAE Tour, Formula One’s Grand Prixes in Bahrain, Azerbaijan and Saudi Arabia, and tennis’ China Open.

This is not to say that only China and Gulf States have drawn condemnation for engaging in sportswashing. Russia hosting the 2018 FIFA World Cup and Hungary hosting a Grand Prix and Euro 2020 football matches represent European examples.

State-funded sportswashing also operates through government-owned entities purchasing or sponsoring teams and competitions. Newcastle United was bought by a group led by Saudia Arabia’s Public Investment Fund in 2021 and this was widely described as sportswashing. In Australia, Qatar Airways sponsor the Sydney Swans and City Football Group sponsor Melbourne City, both of which are companies owned by Gulf royal families.

There are great benefits to sports and local economies when countries host global events and invest in athletes. Is sportswashing that bad?

Huge investments increase the profile of sports and sportswashing can backfire by drawing unwanted negative attention to a country’s human rights record. It can also be asked why western democracies are not called out as sportswashers for their human rights breaches (consider Australia’s ongoing treatment of refugees), and whether countries are just making prudent investment decisions. These points are all true to some extent. However, not only is there a real difference between countries on a scale of oppression, none of these positions should lead us to complacency – injustice needs to be called out regardless of location, financial implications or sporting consequences.

Saudi Arabia's human rights record has been thrust into the international spotlight after its decision to financially back the new LIV Golf series. What human rights obligations do countries like Saudi Arabia have and can they be enforced?

Amongst other issues, (including limited recognition of migrant, LGBTQ+ and women’s rights), freedom of expression, association and assembly are severely curtailed in Saudi Arabia. It is alleged that not all those responsible for the 2018 murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi have been brought to account. The Saudi-led coalition persists in its airstrikes on civilian targets in Yemen, which have been described as war crimes.

Continuing to use Saudi Arabia as an example, these issues are breaches of its international law obligations. The country is party to several human rights conventions, such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT). However, these obligations lack holistic domestic implementation (e.g. are interpreted to have limited effect due to conflicts with domestic Sharia law) and often do not include access to convention-specific optional UN complaint procedures.

Complaints can be taken to the UN Human Rights Council or country disputes to the International Court of Justice, but implementation of any UN findings still lay with the parties (and many countries have not accepted the Court’s jurisdiction, including Russia, China, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Israel or the UAE).

International law is notoriously hard to enforce.

Do professional athletes have a role in protecting or speaking out on human rights? Should they care about sportswashing?

If the United Nations cannot effectively respond to human rights concerns, can athletes? Naomi Osaka wrote during the Black Lives Matter movement that “Today […] athletes have platforms that are larger and more visible than ever before. The way I see it, that also means that we have a greater responsibility to speak up.”

Osaka acknowledges the privileged position athletes occupy. Others, such as boxer Anthony Joshua, have downplayed their role: “All that allegation stuff, for me, I’m not caught up in any of that stuff. I’m here to have a good time, mix with the local people, bring entertainment to Saudi.”

While some high-profile golfers, such as Rory McIlroy, have spoken out against colleagues joining the Saudi-backed LIV Golf series, LIV Golf’s CEO and former world no. 1 golfer Greg Norman has argued that no country is innocent of human rights violations and therefore he is not complicit in Saudi sportswashing.

There is no legal obligation for athletes to care about sportswashing, nor should there be. However, if Osaka is right, then those with a greater platform have a larger social responsibility to speak out on human rights issues. Much recent media attention has been on athletes’ willingness to compromise moral ground to gain financially. International sporting bodies also bear responsibility to discourage sportswashing, by selecting reputable host countries, sponsors and purchasers and should act in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

Yet perhaps it is the public that holds ultimate power, and therefore responsibility, over whether sportswashing investments are successful or not. The popularity of events, games, teams and athletes will decide if authoritarian countries persist in salvaging reputation via marketing rather than real reform. Many fans wish for sport to remain separate from the political sphere, but that does not coincide with reality given sportswashing’s almost universal presence. Until that time, athletes, advertisers, the media and governing bodies should care about sportswashing as it hides the abuse of fellow humans – but so should we.

Austin Irwin was a Human Rights Defender intern with the Australian Human Rights Institute in Term 2, 2022.